The True Cost of Going Public

If direct listings get cheaper and faster to do, would companies go public sooner?

TL;DR: Airbnb and Snowflake likely spent more than 2x Palantir and Asana going public, and may have left billions of dollars on the table by issuing shares before listing their stock. Would companies be better off decoupling their fundraising and listing decisions? If direct listings get cheaper and faster to do, would companies get to public markets sooner?

What does it cost to publicly list a company in 2020? In this post, we’ll take a look at two direct listings, Palantir and Asana, and compare them with two IPOs, Airbnb and Snowflake.

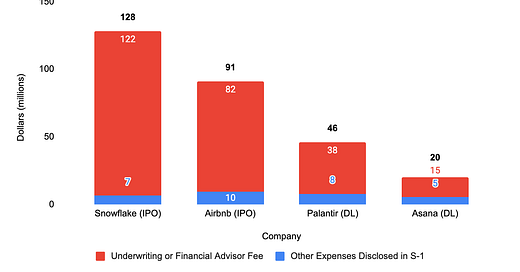

Listing Costs

Each company’s S-1 filing is a good starting point because issuance and distribution expenses are disclosed (item 511 of the registration statement):

At first glance, it looks like its cheaper to run an IPO, but this is misleading because Item 511 asks companies to disclose all expenses in connection with the issuance and distribution of the securities to be registered, other than underwriting discounts and commissions. The underwriting costs from the IPOs are in the prospectus, as separate filing (Form 424B4). For direct listings, “Other advisor fees” include financial advisors or market makers and are analogous to underwriting fees in IPOs.

Underwriting costs are sizable! PwC estimates underwriting fees start at 7% of IPO proceeds and can come down to 3.5% for deals over a billion dollars. It’s estimated that Saudi Aramco, one of the largest IPOs ever with a $26 billion raised, negotiated underwriting fees down to 1% of the offering. Airbnb and Snowflake each raised about $3 billion in their IPOs, paying 2-3% to the bankers. We see different picture after including underwriting fees: Airbnb and Snowflake spent more than twice as much on their listings as Palantir and Asana did.

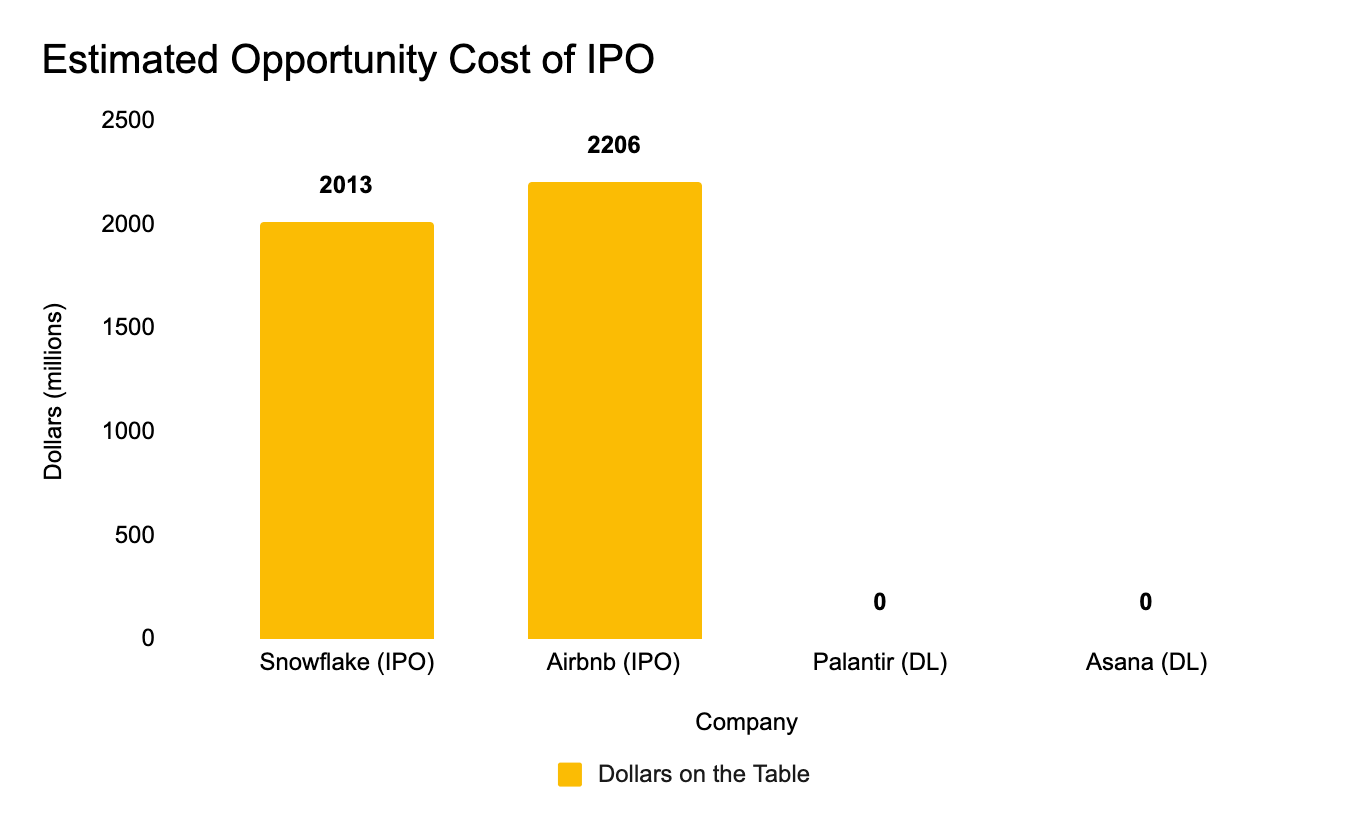

Money on the Table

So IPOs look significantly more expensive than direct listings even before getting into IPO pop, which is the difference between the price the company sells its stock to the bankers (to be flipped to the bankers’ customers) the night before trading and the opening trade in the open market, where the bankers’ customers start trading.

Airbnb and Snowflake sold their IPO shares at $68 and $120 respectively, then subsequently opened at $146 and $245. It’s natural to think about how much more money the companies could have raised if the IPO priced at the opening price, but this is likely oversimplification. Just because the first Snowflake shares traded at $245 doesn’t mean they could have sold all 32 million registered shares for $245.

Imagine an alternative scenario where the companies did a direct listing and followed it up with a follow-on offering at some later date (at the moment you cannot simultaneously do a direct listing and raise funds):

Direct List the company. Assume a direct listing would price at the midpoint of the IPO price and opening trade (IPO pop) price. This is arbitrary, but more conservative than assuming a direct listing would price the same as the first trade in an IPO.

Issue new shares in a follow-on offering at the midpoint price. This is also a simplifying assumption, we’ll ignore changes in the stock price between listing day and the follow-on offering as well as price discounts related to doing a large follow-on offering.

Under these assumptions, Snowflake and Airbnb would have raised an additional $2 billion and $2.2 billion respectively.

Implications

Two things jump out to me after going through this exercise -

The traditional way of going public, IPO, strongly couples the technical process of listing the company on publicly exchange and the process of raising funds. Direct listings show us that these can be decoupled. Companies in a strong financial position could raise capital before (as Palantir did in June 2020) or after listing in a follow-on offering. It’s possible that banks perform an essential service to get the word out about a company and perform a marketing function in the road show, but it’s also possible (especially in the current rate environment) that investors are going to chase any new companies hitting the market with decent financials and a strong growth story.

The 4 direct listings to date cost $20-50M and are significantly cheaper to execute than big IPOs. Maybe it’s possible to make direct listings cheaper over time. If it only cost $10M and three months from start to finish to enter the public markets, would we see companies entering the public markets sooner to access cheaper capital and debt?

Sources

Background Reading